Learning from Neighbours'Experiences: Property Law and Consumer Credit

22/2014

ISBN 978-9985-870-34-1

Issue

The aim of the article is to provide an overview of the legal framework for regulation of SMS‑based credit in Latvia, to assess its effectiveness, and to analyse the relevant case law. The author discusses the effectiveness of licensing of SMS creditors and debt-collection companies. It is concluded that the licensing has facilitated uniformity and improvement of the conditions of consumer contracts, also creating limitations in the realm of advertisement and to the activities of collection services. For example, Latvian law imposes specific restrictions on the advertisement of SMS loans. One of these is that the advertisement may not encourage irresponsible borrowing, and the law sets forth a prima facie list of examples of advertisement encouraging irresponsible borrowing. Also, the SMS creditors’ activities are subject to rules designed for prohibition of unfair commercial practices.

Keywords:

consumer loan; unfair commercial practices; responsible lending

1. Introduction

In Latvia, SMS creditors conquered their market share at the end of 2008 as, in response to the various financial crises, the banks reviewed their credit policy, setting stricter requirements. In consequence, SMS credit became more readily accessible than bank credit and there was no necessity to secure the latter. Since then, SMS credit has become very popular among consumers. For example, in the first half of 2013, non-bank creditors issued SMS credit for, in total, EUR 97 million. *1 At the time of writing, there are 54 licensed non-bank creditors in Latvia. Of these, 20 are distance creditors (SMS creditors), 19 are creditors against pledges (pawnshops), 16 are consumer creditors (providing payments by instalment for goods or services), 15 handle leasing, and 12 are mortgage credit providers. *2

The SMS credit industry is strictly regulated in Latvia; however, as is explained below, the creditors create new business strategies and tactics and, therefore, are usually a few steps ahead of the legislator. Moreover, the legislation process is long and complicated, so the problems in the industry are not solved on the spot. Accordingly, the aim of this article is to provide an overview of the legal framework regulating SMS credit in Latvia, to assess its effectiveness, and to analyse the relevant case law.

2. Legal and institutional overview

The Consumer Rights Protection Law *3 sets forth Latvia’s general rules on consumer credit (in Article 8). With this law, also Directive 2008/48/EC *4 was implemented in Latvia; however, even though that directive excludes from its scope those credit agreements involving a total amount of credit less than EUR 200 (in Article 2, part 2 (c)), the Consumer Rights Protection Law does apply to such agreements (see Article 8, part 4 3 (1)). On the basis of the latter law, numerous regulations of the Cabinet of Ministers have been adopted: Regulations on Consumer Credit *5 , Regulations Regarding Distance Contracts for the Provision of Financial Services *6 , and regulations on the licensing of consumer creditors. *7

In addition, the Unfair Commercial Practice Prohibition Law *8 lays down the main principles for commercial practices in business-to-consumer relations, also affecting the consumer-credit landscape. In 2012, Parliament adopted the Law on Extrajudicial Recovery of Debt *9 , providing for, inter alia, the rights and duties of creditors and debt‑recovery service providers in the recovery process. It was on the basis of this law that the Cabinet of Ministers issued Regulations on Licensing of the Debt Recovery Service Providers *10 and Regulations on Allowed Amount of the Debt Recovery Expenses and Non- Compensable Expenses. *11

There are also other laws applicable to consumer–creditor relationships. For example, the Civil Law *12 sets forth the main principles of contract law, including those pertaining to legal penalties, legal amounts of interest, etc.

According to the Consumer Rights Protection Law, supervision and control of consumer rights’ protection is implemented by the Consumer Rights Protection Centre (see Article 24). *13 The Consumer Rights Protection Centre assesses complaints and other submissions received from consumers, supervises markets for unfair commercial practices, controls the consumer-credit market, and issues special licences for consumer-credit service providers. The centre has issued guidelines on evaluation of consumers’ ability to repay credit to non-bank creditors *14 , on fair commercial practice for consumer credit *15 , and on drafting of fair consumer-credit agreements. *16 Those guidelines state the general principles related to consumer credit but do not constitute an official interpretation of the legal norms, even though in practice creditors should follow those guidelines since they express the views of the supervising institution, the Consumer Rights Protection Centre. Moreover, the guidelines usually are accepted long before the relevant changes in the law are made, so they bridge the legislative gaps and set detailed rules specific to the field of credit. The clear tendency on the Latvian legal scene is for the law to regulate all situations in detail, with it not being deemed sufficient to endorse recommending or explanatory documents.

In general, it must be admitted that the legal foundation for regulation of SMS credit is fragmented and subject to frequent amendments. Accordingly, the body of related laws becomes immense and difficult to perceive. Furthermore, the amendments are adopted post factum—i.e., after events have aroused public interest or discussion in this field, as described below.

Statistics

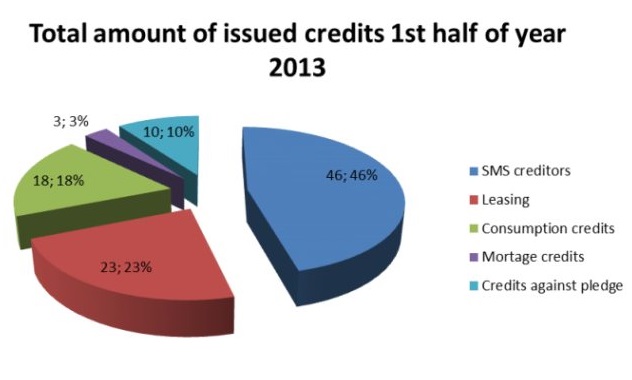

Licensed creditors are obliged to submit information on the consumer-credit agreements concluded, the total sum of the credit issued, and default payment amounts, along with other information, to the Consumer Rights Protection Centre twice per year—by 1 March and 1 September. *17 According to statistics gathered by the Consumer Rights Protection Centre, creditors issued credit to consumer in the total amount of EUR 209.595 million in the first six months of 2013, with EUR 97 million, or 46%, of that taking the form of SMS credit (see Figure 1). *18 This is 59.38% more than the amount of credit issued in 2012.

It has been established that 77.53% of consumers repay the credit without delay; however, 7.92% delay by up to 30 days and 14.55% are in default on payment for more than 30 days. *19

Figure 1. Total amount of issued credits 1st half of year 2013 *20

The statistics show that SMS creditors are still playing an important role in the market; only a small decrease in the amounts issued can be observed as public discussion of the problems related to SMS credit continues and stricter rules on evaluation of the creditworthiness of the relevant consumers are adopted.

3. Measures

3.1. Administrative measures

Licensing

In 2010, there were around 316 companies providing consumer credit in Latvia. *21 With the purpose of facilitating more effective supervision of the consumer-credit market, to introduce unified criteria for such companies, and to protect consumers, the authorities introduced a licensing scheme for providers of consumer credit, in 2011. The consumer‑credit providers had to increase the share capital of their companies to EUR 425,000 *22 and had to obtain a special licence, for a fee of EUR 71,140. Consumer creditors shall re‑register every year, and the state fee for this re-registration is EUR 14,255. The Consumer Rights Protection Centre grants a licence if the company in question has been registered with respect to its processing of personal data in line with the terms set forth by the Data State Inspectorate *23 , the capital company has developed internal procedures for the provision of consumer-credit services and evaluation of the creditworthiness of the relevant consumers, it does not have tax debts, etc.

The licence can be suspended if, for instance, the company does not provide this information, and the requested documents; does not co-operate with the Consumer Rights Protection Centre in order to rectify violations of consumer rights; or does not comply with the requirements of the regulations in force with respect to the protection of consumer rights (see Article 38 of the Regulations on Licensing the Consumer Creditors *24 ). If the company rectifies the violations, the centre renews the licence within 10 working days (according to the terms of Article 40).

Also, the licence can be cancelled if the company significantly violates consumer and personal data protection etc. (under Articles 42 and 43). If its licence is cancelled, the company may file a submission for the receipt of a new special licence no sooner than three years later (see Article 48). No cases of suspension or cancelled have been reported yet.

It must be acknowledged that the licensing, firstly, has made the SMS credit market more transparent; inter alia, the creditors shall submit information about their business activities. Secondly, uniform requirements for creditors were introduced with the licensing system. Before the issuance of a licence, the Consumer Rights Protection Centre evaluates whether the relevant creditor can fulfil all legal requirements related to consumer protection, such as ensuring that any unfair contract terms have been eliminated; thus creditors are forced to have their contracts, internal regulations, and processes in order. For instance, prima facie illegal terms are excluded from the credit contracts, as the Consumer Rights Protection Centre evaluates the standard contracts before issuing a licence; thus, the centre effectively and actively supervises SMS credit.

Marketing/advertising restrictions and unfair commercial practices

In their first form, the Regulations Regarding Consumer Credit Agreements provided that credit advertisements *25 shall not encourage irresponsible borrowing and that all advertisements shall contain information warning consumers to borrow responsibly and to evaluate their ability to repay the credit (see Article 14). *26 In practice, as established by the Consumer Rights Protection Centre, the warning about responsible lending shall not be in a smaller font size than other text in the advertisement; otherwise, the warning does not fulfil its aim. *27

However, the newRegulations on Consumer Credit *28 provide instead that the advertisement shall not encourage irresponsible borrowing (see Article 11). For determination of whether an advertisement encourages irresponsible borrowing, the overall content and the way it is presented, its design, and the information provided in the advertisement on the credit service that enables the consumer to take an informed and economically justified decision shall be taken into consideration.

The new regulations do not directly require inclusion of a warning related to responsible lending. Nonetheless, the creditors still use this warning in their advertisements, and it plays an important role in evaluation of the content of the advertising, as is proved by the case of an advertisement with the slogan ‘So easy!’. The latter advertisement was acknowledged as not conforming with professional diligence, as it promoted irresponsible lending even though it did also present a phrase reminding the reader to borrow responsibly. *29 The Consumer Rights Protection Centre concluded that the overall content of the advertisement and its presentation established the notion that the credit could be taken out easily and quickly, and that undertaking the credit obligations is hassle-free and not connected to any risks.

In an other case, the consumer creditor’s advertising spread stated that a client who borrows at least LVL 150 (~ EUR 214) gets an invitations to the concert Love in the Right Moment as a gift. *30 It was promised that the most well-known musicians would participate in the event, and concert tickets could not be bought on the open market. Firstly, the Consumer Rights Protection Centre established that advertising is part of consumer creditor’s commercial practice. *31 Then, the centre decided that, since tickets were distributed to many consumers, this advertisement influenced consumers’ economic behaviour. Furthermore, the advertisement did not indicate that the consumer undertakes financial obligations by receiving the credit and that the credit should be paid back with interest. Accordingly, such advertisement facilitates irresponsible lending, with consumers not evaluating whether such credit is necessary at that point and whether the credit can be paid back on time, without creating financial problems. In this case, the credit company argued that the new regulations do not mandate that advertisements include a warning about responsible lending. The Consumer Rights Protection Centre agreed that the warning is indeed not mandatory, after accepting new amendments; however, even if such a warning is included, the advertisement in question can facilitate irresponsible lending—Article 11.1 of the new regulations states that, for determination of whether there is facilitation of irresponsible lending, all information on the credit service provided in the advertisement that enables the consumer to take an informed and economically justified decision shall be taken into consideration. As the above-mentioned advertisement motivated consumers to take out credit irresponsibly, the company’s commercial practice was misleading. The centre imposed a monetary penalty on the relevant SMS creditor.

The cases described above show that creditors use powerful advertisement tricks that often can be considered aggressive commercial practice or misleading advertisement. Additionally, most likely in consequence of the above-mentioned cases and similar ones, further amendments to Regulations on Consumer Creditwere adopted. *32 Those amendments describe prima facie examples of advertisement that promotes irresponsible borrowing. For example, an advertisement that calls on the reader to take out credit without considering its necessity and regardless of the consumer’s finances or implies that there is no risk when one takes out credit shall be considered to be advertising of irresponsible borrowing (under Article 11.1). The regulations state that encouragement of irresponsible borrowing in advertising occurs also when the creditor offers, in addition, goods, services, or other preferences besides the credit itself. If the creditor violates such rules, the Consumer Rights Protection Centre, taking into consideration the character and nature of the violation, can require the creditor to ensure the conformity of its advertising, with adverts in full accordance with the law *33 , or can apply administrative sanctions. For example, the administrative fine for legal persons distributing an advertisement not conforming to the requirements of regulatory acts can range from EUR 70 to 14,000. *34

The system for debt collection

Out-of-court recovery

Taking into consideration the number of consumer complaints about the methods and costs of out-of-court debt recovery, Parliament adopted the Law on Extrajudicial Recovery of Debt *35 in 2012. This law is applicable to creditors and licensed out-of-court collection companies (see Article 1). The aim of the law is to provide fair, proportional, and reasonable debt collection (Article 2). For example, it sets general rules for the culture of communication with the debtor—aggressive and offensive communication is forbidden; the debtor shall not be visited at his or her place of employment or residence without prior consent; and communication shall not be performed on Sundays, public holidays, or between 9pm and 8am (see Article 10).

Out-of-court collection companies shall be required to obtain a licence issued for a three‑year term by the Consumer Rights Protection Centre (under Article 5), and the state fee for the issuance of this special licence is EUR 3,555, with renewal costing EUR 1,420 per year. *36 Before adoption of the law, there were 67 companies in the collection business *37 , whereas now there are only 22 companies so licensed. *38

New regulations also limit collection costs. *39 Collection companies shall not collect more than seven euros for the written announcement of the debt and invitation to the consumer to pay the debt and not more than EUR 10 for other collection activities (under Article 2). The actual costs incurred in debt collection, however, are much higher that the cap set by the legislator.

Positive changes can be identified that have arisen from licensing of this sector. Creditors and debt-recovery companies are required to follow the quality standards that are set forth by law, and the collection costs borne by the consumer have significantly decreased. However, the law still does not cover questions related to the secondary collection process—for example, when the creditor moves the collection case from one collection company and forwards it to another.

In-court debt collection

Many disputes with consumers were resolved in arbitration until 2006. Then, with the implementation of the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Directive *40 and in line with European Court of Justice practice *41 , the arbitration clause of many consumer contracts was acknowledged as unfair. Accordingly, most such disputes cannot be handled via arbitration anymore. *42

Even though creditors can use court proceedings of various types for purposes of recovering the debts from their clients, court proceedings are not effective, in general, and they are time-consuming and rather expensive.

For example, the Civil Procedure Law *43 provides for special procedure—the compulsory execution of obligations in accordance with a warning procedure (the national equivalent of a European Order for Payment). This procedure shall apply only in those cases wherein the declared address of the debtor is known and the contractual penalty and interest together do not exceed the initial debt (see Article 406 1 ). The procedure is based on standard forms, it is a written process, and no court hearings are held. If the respondent does not submit objections to the claim but has received the warning, the court decides in favour of the claimant and the decision is forwarded directly for compulsory enforcement. This procedure is quicker and less expensive—with a state fee of two per cent of the debt but not more than EUR 498.01—than other available procedures. However, it is not very effective, as in most cases the debtor responds to the claim and disputes it; therefore, the case should be dismissed, because Article 406 7 of the Civil Procedure Law specifies that debtor objections submitted within the prescribed time period with respect to the validity of the payment obligation shall be the basis for termination of court proceedings related to compulsory execution of obligations in accordance with warning procedures. In these cases, the creditor can then apply the ordinary procedure.

In 2011, a small-claims procedure was introduced in the Civil Procedure Law. *44 The aim with this procedure was to expedite and simplify the resolution of small claims (claims for up to EUR 2,100), by means of a standard-form-based and mostly written procedure; however, the case materials available to the author of this article indicate that resolution of the disputes usually takes more than a year and that oral hearings are held in most cases. Therefore, the initial aim with the procedure is not met.

The ordinary civil procedure is seldom used for recovery in cases of consumer credit: it is even more time-consuming than the small-claims procedure. Moreover, the court fee is the same as for the small-claims procedure; i.e., if the claim is up to EUR 2,134, the court fee is 15% of the claim but not less than EUR 71.44 (under Article 34 of the Civil Procedure Law). Clearly, both procedures are very expensive for recovery of small debts. Moreover, compulsory enforcement of the judgement is not always successful, since the debtors may not have any income or may become insolvent. Accordingly, creditors use mostly the services of collection companies in their attempts at recovery from their clients.

Positive- and negative-credit registers

Until 2012, credit databases were not regulated by Latvian law; however, the Law on Extrajudicial Recovery of Debt *45 introduced special requirements applicable to negative‑credit databases. According to that law, the debtor shall be included in a negative-credit database only if having delayed payment for more than 60 days. The information may be stored in the database for three years from the moment at which the debt is paid; otherwise, the information is stored in keeping with the statute of limitations, for 10 years (see Article 13).

A third party may receive information from such a database if there is an agreement concluded between the creditor and the third party and also if the debtor has indicated acceptance in accordance with the Personal Data Protection Law. *46

In practice, each SMS creditor and debt-recovery company keeps its own credit database. In parallel, the Bank of Latvia maintains its own credit register. *47 Consequently, there is no single uniform register of negative and positive credit, so highly objective information can not always be received about a prospective client.

Responsible lending obligations

As is indicated above, creditors shall not encourage irresponsible lending in their advertising, and regulations provide for a non-exhaustive blacklist of advertisers that prima facie promote irresponsible lending. The list covers the following situations: inviting a consumer to take out credit without considering its necessity and reasonability or without regard for his or her financial situation; creating the impression that receipt of the credit is without risk or that credit can solve all of one’s financial problems; and influencing the consumer’s decision to take out credit by offering additional services, goods, or other benefits. *48 Also, the Consumer Rights Protection Centre can impose administrative fines for such violations. *49

Referring to materials from the European Commission *50 , the Consumer Rights Protection Centre indicates in its guidelines *51 that the target group of credit advertising is composed of vulnerable consumers. These consumers are more susceptible to a commercial practice or product because they are credulous; therefore, they readily believe in offers of quick and risk-free credit. The author of this article argues that, thanks to awareness and publicity of the issues associated with consumer credit and the experience of large numbers of consumers, the target group of such advertisement shall be identified as average consumers. Moreover, the consumer too should take responsibility in the process.

The obligation to assess creditworthiness

Pursuant to Article 8, part 4 1 of the Consumer Rights Protection Law, the creditor is obliged to assess the creditworthiness of the consumer before conclusion of a credit agreement. *52 When evaluating the creditworthiness of a consumer, the creditor shall take into account, firstly, the sufficiency of the information provided by said consumer. Such information includes income, employment, other characteristics (such as age, education, and civil status), etc. as indicated in the guidelines issued by the Consumer Rights Protection Centre. *53 If the credit is for less than EUR 427 and monthly payments do not exceed EUR 71, the creditor is permitted to rely only on the information given by the consumer. However, if the amount is greater, the SMS credit provider shall, secondly, evaluate the relevant credit history in credit databases or in other databases. If refusal to issue credit is grounded in the data obtained from databases, the creditor shall inform the consumer immediately of the result of said consultation and of the particulars of the database(s) consulted, without charge. The creditor’s failure to assess the consumer’s creditworthiness constitutes an unfair commercial practice and non-conformance with professional diligence. *54 The Consumer Rights Protection Centre may impose fines on legal persons in this connection, from EUR 70 to 14,000, in accordance with the Latvian Administrative Violations Code. *55

One reason for introduction of the obligation to assess the consumer’s creditworthiness was the aim of restricting the possibility of issuing SMS credit immediately after application by the consumer. For example, it is suggested that 15 minutes is too little time for full evaluation of the consumer’s creditworthiness. *56 Nonetheless, SMS credit can be received very quickly.

In practice, the argument that the creditor has not completed an evaluation of creditworthiness is the justification most often used by consumers in default. In the debtor’s mind, the deal should, in consequence, be considered void. However, many of the consumers in this category have, firstly, supplied their employment records and salary amounts when registering for the credit, so that the creditor can assess the creditworthiness of the prospective client on the basis of the information provided. Secondly, most of these consumers have previously taken out credit with the same provider and, more importantly, paid back the sums on the required date or even earlier. Therefore, consumers cannot rely on the argument that the creditor has not evaluated their creditworthiness. *57

3.2. Contractual measures

Regulations Regarding Distance Contracts for the Provision of Financial Services *58 is a set of rules prescribing the information to be included in a distance agreement for the provision of financial services, specifically SMS credit. Namely, the agreement with the consumer shall include precise description of the services provided; the total sum to be paid, including all expenses and commission fees; the payment terms; the obligations and rights of the parties; etc. In general, almost all SMS creditor offer very similar contract terms, except with regard to the fees, APRC, contractual penalties, and interest.

Contractual penalty

The issue of contractual penalties is one of the most topical questions in the Latvian legal environment, so it is appropriate to describe the historical evolution of the legal norms related to penalties.

Initially, the Civil Law did not set any limits as to the amount of contractual penalties, stating that the contracting parties themselves shall determine the amount of these and that it is not limited to the amount of the losses expected as a result of non-performance of the contract (see Article 1717). *59 In practice, creditors and collection companies were collecting penalties from debtors not only for the delayed payments but also for other breaches of the credit contract. Consequently, the amounts of the penalties were excessive in many cases. For example, someone concluded a credit agreement for EUR 213 on 6 May 2004 and the contractual penalty for delayed payments as of the moment when the consumer submitted a complaint to the Consumer Rights Protection Centre (on 18 December 2006) was EUR 7,466. *60

The special law—in the form of the Consumer Rights Protection Law—provides that terms of contract that impose disproportionately large contractual penalties or other compensation for non-performance or unacceptable performance of the contractual obligations shall be deemed unfair and shall not be in force from the moment of entry into the contract (under Article 6, parts 3.4 and 8). Accordingly, the Consumer Rights Protection Centre has always paid special attention to the calculation of penalties under credit contracts. The centre has stipulated that, to establish whether a penalty is proportionate and grounded, one shall take into account the following criteria: the payments and their amounts (for example, whether the penalty is calculated from the debt sum or the total value of the agreement); the significance of the consumer’s breach of contract (for example, the penalty being imposed if the client has not informed of a change of address), whether the contract provides for a ceiling to the contractual penalty and whether or not penalties are imposed doubly for the same breach (for example, for delayed payment and for a reminder letter about delayed payment). *61

However, even though most SMS credit contracts provided a reasonable formula for calculation of the contractual penalties, consumers received debt computations with contractual penalties in the same amount as the initial debt or even more. Because of lack of the knowledge, time, or money necessary, most consumers did not turn to the courts for the protection of their rights and did not object to the excessive penalties. Many complaints still were received by the Consumer Rights Protection Centre *62 , though. Consequently, more changes were made in the relevant article of the Civil Law, in 2009. The legislator adopted a new Article 1724 1 , providing that the courts shall reduce the penalty to a reasonable amount if it is excessive. In applying this provision of the law, the case law suggested that a contractual penalty is reasonable if it does not exceed the main debt. *63 However, the debt recovery was done primarily by collection companies, not the courts (the latter having the power to assess the reasonableness of the penalties), so still the companies calculated contractual penalties that exceeded the original debt.

Therefore, proposed changes related to contractual penalties were again put before Parliament for consideration. Article 1717 of the Civil Law was amended to state that a contractual penalty for delayed or incomplete obligations shall not exceed 10% of the initial debt or the total value of the contract. *64 Remarkably, despite the fact that this norm entered force on 1 January 2014, it is to be applied also to those contracts concluded before that date and executed on or after 1 January 2014 and if the claim regarding the contracts is not submitted to the court until 31 December 2014. *65 Moreover, these legislative changes pertain also to the order of debt extinguishment. Namely, a creditor previously could offset the debtor’s payment first in terms of interest and contractual penalties, then with regard to the original debt, but with the latest changes, the contractual penalty shall be the last debt extinguished (see Article 1843). *66

Three important consequences emerge from the latest amendments to Article 1717 of the Civil Law. Firstly, the amendments apply not only to consumer-to-business but also to business-to-business relations. This is regrettable. Restriction of contractual penalties could be more explicitly regulated in the special consumer laws, thereby allowing the possibility for free and unlimited agreement in business-to-business contracts as to the amount of penalties. Secondly, consumer-credit providers started to change the clauses on contractual penalties into late-payment interest clauses in their credit contracts, since the amount of late-payment interest is not as limited as that of contractual penalties (see the next section of this article). Thirdly, the courts reduce contractual penalties to 10% even for those consumer contracts concluded before the amendments were introduced, yet such decisions are not in line with European Court of Justice case law, which specifies that national courts shall render the unfair clause invalid and that the national courts are precluded from actually modifying the relevant contract by revising the terms’ content. *67

Interest

According to the general norm incorporated into Article 1753 of the Civil Law, interest is compensation either to be given for the use of a sum of money or to be submitted in consequence of late payment. The idea of interest as set forth in the Civil Law is to provide the important equivalence of the market economy—i.e., capital shall bring forth additional capital. Interest is not meant as punishment. Unlike a contractual penalty, it is encouragement to settle one’s obligations in an expeditious manner. *68

In practice, however, interest is also used as the price for default, especially with SMS credit. As is indicated above, after the amount of contractual penalties was limited to 10% of the basic debt under the Civil Law, most of the SMS creditors changed their terms on contractual penalties into late-payment-interest clauses in the contracts because the Civil Law provides that interest for late payment stops growing only upon reaching the amount of the capital (see Article 1763), so the creditors can claim more in interest than in penalties. This problem has been acknowledged by the courts. *69 Consequently, the new changes in the law provide that inadequate interest and also interest that contravenes the principle of fair dealing shall be illegal (see Article 1764). *70 Therefore, if the court considers the interest inadequate, it may exercise its initiative and declare this clause of the contract to be void.

As can be seen from the foregoing discussion, diverse questionable practices in the consumer-protection field ended with the introduction of stricter rules in the body of general laws, and, furthermore, the rules shall apply not only to consumer contracts but also to commercial agreements, of whatever sort.

APRC

An appendix to the Regulations on Consumer Credit *71 provides a formula for calculation of annual interest rates; however, the law does not actually restrict this rate. According to information provided by the Ministry of Economics, each creditor sets its own limits and some of them have rates that even start at 120% and reach 1552% (except for the first credit). *72 There have been legislative initiatives to limit the total amount of annual interest, but so far these have been without any success.

3.3. Penal measures

The Criminal Law *73 stipulates the general criminal responsibility of consumer-targeting service providers with respect to services that do not correspond with the quality standards set (see Article 202). Article 201 of the Criminal Law bans usury, specifying that any kind of lending activities performed by taking advantage of the borrower’s difficult material situation and by setting excessively burdensome conditions shall be penalised with short-term detention (up to three months) or forced labour or with a monetary penalty. However, there are no cases reported yet of application of this norm.

4. Conclusions

Latvia not only introduced harmonisation of the Directive on Credit Agreements for Consumers *74 in accordance with the scope set forth in Recital 10 of its preamble but also enacted stricter rules pertaining to consumer credit. However, almost every outburst in the sphere of regulation of SMS credit results in amendment of the law. Thereby, the legal framework is changed too often and rules addressing SMS credit can be found in many, quite different laws, regulations, and guidelines.

In Latvia, SMS creditors are required to be licensed, and currently there are 20 SMS creditors so licensed by the Consumer Rights Protection Centre. The licensing scheme for SMS creditors has facilitated the adjustments of the SMS credit sector, since the creditors are required to follow strict rules and guidelines. The system includes unification and improvement of consumer contracts, along with limitations to advertisement content and the use of collection services. Moreover, SMS creditors shall submit statistics and other information related to credit twice per year, thereby rendering it possible to estimate the market share of SMS creditors, numbers of borrowers, and their level of payment discipline.

Latvian law sets in place specific restrictions to the advertisement of SMS loans; for example, advertisements may not encourage irresponsible borrowing, and a non-exhaustivelist of examples of advertisement types that encourage irresponsible borrowing is provided in the law. Also, SMS creditors’ activities are subject to rules aimed at prohibition of unfair commercial practices.

Debt-collection services too are subject to licensing in Latvia, so a strict set of rules is in place, providing a standard for communication between creditors, collection agencies, and debtors. The law also specifies rules for the establishment and maintenance of negative-credit databases and sets forth maximum limits to the costs that may be claimed from the consumer for collection services.

The legislator has amended the Civil Law so as to impose a cap on contractual penalties (10%) for all kinds of contracts, including consumer contracts, and setting limits to the interest rates. However, there are still no restrictions as to APRC or on the amount of the commission for the issuing of credit. Whether stricter is better only the future will show us…

pp.138-148